By Adam Lloyd Johnson, Ph.D.

People have been intimidated by machines for a long time. It’s hard to say when this first began, but it definitely was ramped up during the industrial revolution when machines were taking over more and more jobs. It’s easy to understand why people felt intimidated; machines were superior to humans in certain respects – they were stronger, faster, and more reliable. Computers have only exacerbated this anxiety because now machines can be smarter than humans in certain ways – they can remember more and compute faster. This was strikingly driven home in 1997 when IBM’s computer “Deep Blue” beat World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov. Computers have taken over even more of our jobs; the unnerving threat of being replaced by a machine looms heavy on people’s minds.

Hollywood knows just how to tap into these anxieties. There have been several movie franchises built around the idea of machines taking over the world: The Terminator, The Matrix, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Alien, etc.

In the latter two, machines didn’t try to take over the world per se, only their little corner of it. A central element in both movies is the idea of machines taking a superior position over humans and trying to control their fate. Think of how HAL 9000 tried to kill off Discovery One’s crew in order to preserve his own existence. In Alien, the android Ash considered Nostromo’s human crew expendable if they got in the way of his directive to bring an alien back for research.

In this article I will argue that there is a sense in which machines have already taken over the world. Machines have already destroyed mankind, and in a way that is much more frightening than any Hollywood movie. I’m actually talking about a machine philosophy that has overtaken the world, a philosophy that views human beings as mere machines. This is scarier than The Terminator or The Matrix. This man-is-machine philosophy doesn’t destroy us physically, it does something worse: it destroys what it means to be human; it destroys the essence of what mankind is.

Historical Background

Some history will be helpful here. It’s true that early scientists such as Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton viewed the universe as a vast machine. But they didn’t view mankind as being part of this vast machine; man was outside of the machine, so to speak. Everything else in the universe followed set, deterministic laws of cause and effect, but human beings were different; they were unique, special. Yes, they had machine-like parts. The heart functions like a pump, for example, but humans were more than merely the sum of their machine-like parts. These early scientists didn’t think human beings were governed by deterministic laws of cause and effect; they knew human beings had intelligence, free will, and made real choices.

This thinking changed radically during the 1800s. More and more people began to think that human beings were merely the result of mechanical forces, the laws of nature so to speak. This was a titanic shift. Human beings were now thought of as part of the deterministic chain of cause and effect, part of the universe-machine; hence, they are just machines themselves. The man most responsible for influencing this way of thinking was Charles Darwin.

How has this “man is machine” philosophy affected Western society? How exactly has it destroyed our humanity? Francis Schaeffer is very helpful here. He was a Presbyterian pastor that was highly influential in the 1950s through the 1970s. He published over twenty books explaining how and why Western thinking has shifted over the last few hundred years. In one particular lecture, Schaeffer showed how Darwin’s evolutionary ideas, specifically that humans are just biological machines, affected Darwin’s own personal life. Schaeffer then explained that this foreshadowed well how these ideas would affect Western society over the next 150 years.

Darwin’s Own Words

We can see how this machine philosophy affected Darwin’s own life by comparing the young Darwin with the older Darwin. The following quotes come from Darwin himself and can be found in a book of his letters put together by his son Francis Darwin—Charles Darwin: His Life Told in an Autobiographical Chapter, and in a Selected Series of his Published Letters. The first part of each quote describes Darwin’s view when he was younger, but the latter part of each quote (which I have put in bold text) describes his view when he was older. The first thing to notice is how this machine philosophy moved him away from belief in God.

The Duke of Argyll… recorded a few words… spoken by my father in the last year of his life. “…I said to Mr. Darwin, with reference to some of his… work on the Fertilisation of Orchids… and various other observations he made of the wonderful contrivances of certain purposes in nature – I said it was impossible to look at these without seeing that they were the effect and the expression of mind. I shall never forget Mr. Darwin’s answer. He looked at me very hard and said, ‘Well, that often comes over me with overwhelming force; but at other times,’ and he shook his head vaguely, adding, ‘it seems to go away.’” (pg. 64)

Why Darwin, why did this go away?

The old argument from design in Nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered. We can no longer argue that… the beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door by man. There seems to be no more design in the variability of organic beings, and in the action of natural selection, than in the course which the wind blows. (pgs. 58-59)

He also wrote about the argument for God from a first cause.

Another source of conviction in the existence of God… impresses me as having much more weight. This follows from the extreme difficulty or rather impossibility of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe, including man with his capacity of looking far backwards and far into futurity, as the result of blind chance or necessity. When thus reflecting, I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent mind in some degree analogous to that of man; and I deserve to be called a Theist. This conclusion was strong in my mind about the time… when I wrote the Origin of Species, and… since that time… it has very gradually… become weaker. …can the mind of man, which has, as I fully believe, been developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animals, be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions? …the mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us, and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic. (pgs. 61-62)

It is clear that Darwin moved away from belief in God because of his evolutionary ideas. He used to find theistic arguments quite compelling, e.g., the argument from design or the argument from first cause. In his earlier days, it seemed to him nearly impossible to conceive that our universe, including human beings, could have happened by chance. But later, after he adopted his ideas about evolution, he began to doubt whether he could really trust his mind’s ability to draw correct conclusions. His evolutionary ideas led him to reject his own logical intuitions. Next we will see how his ideas affected his view of mankind.

…the most usual argument for the existence of an intelligent God is drawn from the deep inward conviction[s]… which are experienced by most persons. Formerly I was led by feelings such as those… to the firm conviction of the existence of God and of the immortality of the soul. In my Journal I wrote that whilst standing in the midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian forest, “it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.” I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body; but now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions… to rise in my mind. …I am like a man who has become colour-blind… (pgs. 60-61)

When God is dead, man is dead. Darwin used to think that mankind was something more, something special. But we start to see here how his man-is-machine philosophy destroyed his concept of humanity. This can be seen even more strikingly in how his appreciation for beauty changed.

…in one respect my mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years. Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds, such as the works of Milton, Gray, Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley, gave me great pleasure, and… I took intense delight in Shakespeare… I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also almost lost my taste for pictures or music… this curious and lamentable loss of the higher aesthetic tastes is all the odder… My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive… (pgs. 50-51)

Darwin did not understand why viewing himself as a machine led to a loss of his very own humanity in the realm of beauty and art. When God is dead, man is dead. And as Schaeffer often pointed out, when mad is dead, beauty and morality are dead.

I am glad you were at the Messiah [Handel’s], it is the one thing that I should like to hear again, but… I should find my soul too dried up to appreciate it as in old days; and then I should feel very flat, for it is a horrid bore to feel as I constantly do, that I am a withered leaf for every subject except Science. It sometimes makes me hate Science, though God knows I ought to be thankful for such a[n]… interest, which makes me forget for some hours every day my accursed stomach. (pg. 269)

Science did not kill his humanity. Science is a great and wonderful thing. It was his man-is-a-machine philosophy that killed his humanity. Next, we see how it affected his view of morality.

Whilst on… the Beagle I was quite orthodox, and I remember being… laughed at by several of the officers… for quoting the Bible as an unanswerable authority on some point of morality. (pg. 58)

Many people are surprised to learn that Darwin piously quoted the Bible while on his famous journey. The following quote, which provides his view as an older gentlemen, comes from another section of the book:

The loss of these tastes [for poetry, plays, paintings, and music] is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature. (pg. 51)

Did Darwin reject morality all together? No, he did not.

…I may say that the impossibility of conceiving that this grand and wondrous universe, with our conscious selves, arose through chance, seems to me the chief argument for the existence of God; but whether this is an argument of real value, I have never been able to decide… The safest conclusion seems to me that the whole subject is beyond the scope of man’s intellect; but man can do his duty. (pg. 57)

Within the man-is-a-machine philosophy, God is dead. When God is dead, man is dead. And when man is dead, morality is dead. We see here how Darwin tried to hold onto morality. He recognized where all this was headed, but he tried to fight against the logical conclusion of his evolutionary ideas. He said no, morality will not die because man will do his duty. We can still hold onto morality even though we believe God does not exist and we are merely machines; man can do his duty! But what is this duty, Darwin? Where does it come from?

What Followed

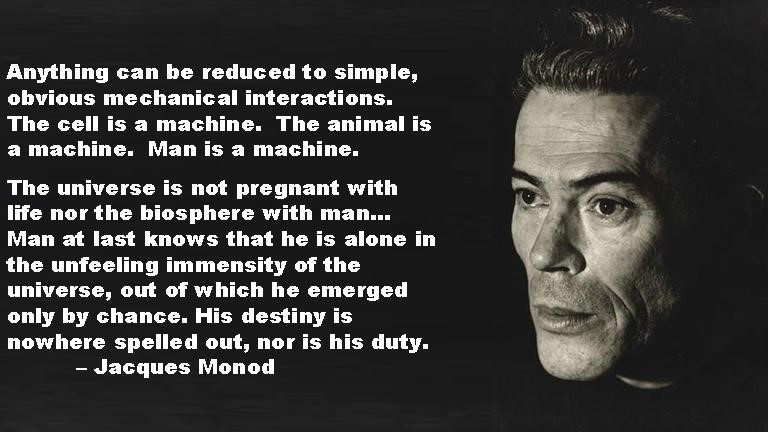

Darwin himself didn’t carry his man-is-machine philosophy to its ultimate conclusion, but those who came later did. Take Jacques Monod, for instance; he was a Nobel Prize winner and one of the founders of molecular biology. He wrote, “Anything can be reduced to simple, obvious mechanical interactions. The cell is a machine. The animal is a machine. Man is a machine. The universe is not pregnant with life nor the biosphere with man… Man at last knows that he is alone in the unfeeling immensity of the universe, out of which he emerged only by chance. His destiny is nowhere spelled out, nor is his duty.” Clearly, he recognized the inevitable conclusion of this man-is-machine philosophy.

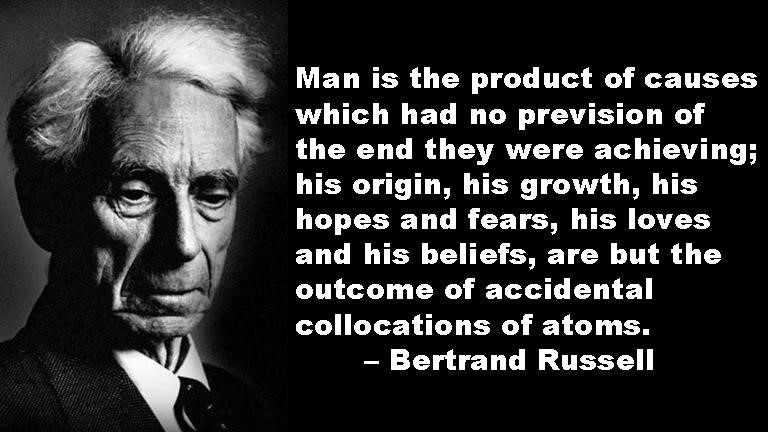

Bertrand Russell, also a Nobel Prize winner, was one of the founders of analytic philosophy and is considered one of the 20th century’s premier logicians. He wrote, “Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms.”

I trust you’re beginning to see how humanity is destroyed by this machine philosophy. In this way of thinking, everything that makes us human, our hopes, fears, and loves, is just the result of random, accidental atoms bouncing around.

Richard Dawkins, probably the most well-known atheist alive today, was a professor at Oxford and has written many well-known books. He wrote, “We are survival machines – robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes. This is a truth which still fills me with astonishment. Though I have known it for years, I never seem to get fully used to it.” I would suggest that he can’t get fully used to it because it cuts across the grain of everything we are as human beings.

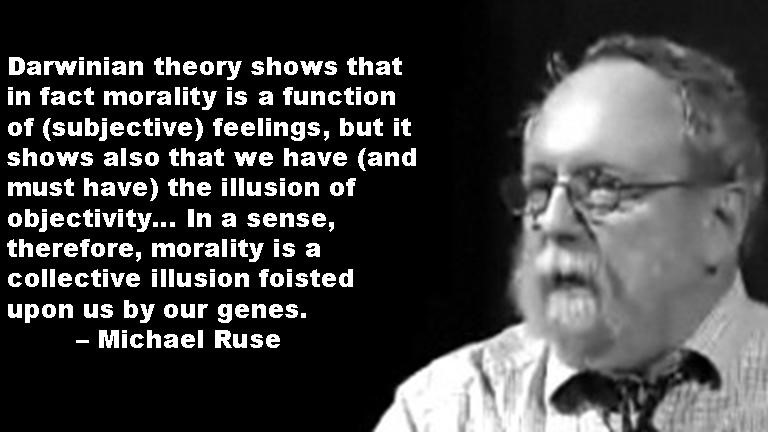

Michael Ruse, a philosopher of science and professor at Florida State University, wrote that “Darwinian theory shows that in fact morality is a function of (subjective) feelings, but it shows also that we have (and must have) the illusion of objectivity… In a sense, therefore, morality is a collective illusion foisted upon us by our genes.”

When man is dead, morality is dead.

Scarier than the Terminator

This is scarier than The Terminator. In fact, this is so frightening that Hollywood can’t even deal with it. What do I mean? More and more movies are portraying machines not as cold, heartless instruments of death but as warm, moral, and able to love. Two recent movies stand out in this regard: Transcendence and Her.

In the futuristic movie Her, released in 2013, Joaquin Phoenix’s character falls in love romantically with his computer’s intelligent operating system, voiced by Scarlett Johansson. This may sound like a silly comedy, but actually it was a very serious drama that won the Academy Award for best original screenplay. In Transcendence, Johnny Depp’s character dies, but, before his body perishes, his mind is downloaded onto a computer. Throughout the movie the audience is led to think that this “mind” in the computer has lost its humanity and has become cold, calculating, and ruthless, like so many other machines in movies. But the plot twist at the end reveals that it was truly him all along, that his computer version actually retained his humanity, i.e., his morality, love, and compassion.

Now I don’t personally know any Hollywood types, so I can’t claim to know their motives. But I do have a theory, and maybe it’s not even that Hollywood thought it through like this consciously; it might just be the thought process that has taken place overall at a cultural level. Regardless, it seems to me like something such as the following has taken place. First, we as a culture produced a string of movies where machines were portrayed as cold, heartless, and unable to love. But then we recognized that, wait a second, we’re just machines ourselves! That’s what many scientists and philosophers are telling us anyway. Biological machines, no doubt, but still machines. Putting one and two together, the conclusion must be that we ourselves are cold, heartless, and unable to love, that morality isn’t real. And this is what many scientists and philosophers are saying, as we’ve seen. Romantic love is just a chemical reaction nature selected because it caused us to reproduce and pass on our genes. Parental love was just programmed into us by evolution so that we would care for our offspring so they could, again, pass on our genes.

The problem is that most of us are like Richard Dawkins, and we find this hard to accept; we don’t like it, it’s too frightening to deal with. We want love to be real; it cuts across the grain of our humanity to say that love is just an illusion, the result of an accidental, random mutation. So we, and Hollywood, are caught in this tension. On the one hand, we have bought into this man-is-machine philosophy because that’s what we’ve been taught. But on the other hand, we so want love to be real. Do you see the despair here? Imagine finding out one day that you’re just a robot, that everything about you has been programmed. You don’t really have free will; all the decisions and choices you think you’ve made were just what you’ve been pre-programmed to do. All your personality traits are just accidental lines of code. Imagine the despair. Your feelings, aspirations, loves, and relationships were predetermined by programming. And you can’t escape. The rest of your life will be just the same; even the feelings you experience in reaction to this news are just the result of your programming.

You may think, “Well, if I could find the programmer who designed me and talk to him, then I could at least find out why he programmed me like this.” But despair is piled on despair because there is no such programmer. There is no person behind who and what you are; you have no creator. Your programming just came about randomly and accidently. There’s no programmer; there’s no maker to go to and ask these “why” questions. You’re just an accident of an unfeeling, uncaring, silent, material universe. Wouldn’t that be crushing? Wouldn’t that make you doubt that there’s even any purpose to life? That maybe you’re not even real, that there is no such thing as you?

Let me review. I’m proposing that something like the following thought process has occurred on a cultural level.

- In movies we portrayed machines as cold, heartless, and unable to really love.

- But then we realized that, wait a second, ultimately we’re just machines too!

- That realization must also mean that we’re cold, heartless, and unable to really love as well.

We could remove the tension by just rejecting #2, by rejecting the man-is-machine philosophy. Instead, we’ve tried to relieve the tension by changing #1. We’ve re-cast machines with the ability to be moral and to love. In effect, we’ve come to tell ourselves that machines can be moral. Therefore, it’s alright that we’re machines because, see, you can be a machine and still experience morality and love.

Even the classic movies we started with (The Terminator, The Matrix, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Alien), the ones famous for their cold, heartless, killing machines, all came back in their sequels with machines re-cast as good, moral, and loving. Again, I believe this was done to relieve the terrifying tension I explained above. In other words, Hollywood could make scary movies about heartless killing machines without any problem. But the idea that that is all we are was too frightening, and so the machines were re-cast. Let me give some examples.

In The Matrix, the machine program Agent Smith tells the human Morpheus, “…when we started thinking for you, it really became our civilization which is, of course, what this is all about. Evolution, Morpheus. Evolution. Like the dinosaur… You had your time. The future is our world, Morpheus. The future is our time.” In the second sequel, Matrix Revolutions, a machine program explains that “I love my daughter very much. I find her to be the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.” Needless to say, Neo was very surprised to hear a machine talk that way.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL is cold, calculating, and ruthless. When astronaut David Bowman asks HAL to let him back into the spaceship so he won’t die, HAL replied with the now famous line, “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.” In the sequel, though, 2010, we’re told that HAL shouldn’t be blamed for what he did. His creator, Dr. Chandra, explained that “it wasn’t his fault… HAL was told to lie… by people who find it easy to lie. HAL doesn’t know how so he couldn’t function. He became paranoid… Whether we are based on carbon or silicon makes no fundamental difference. We should each be treated with appropriate respect.” The message is clear: essentially, machines are just like us.

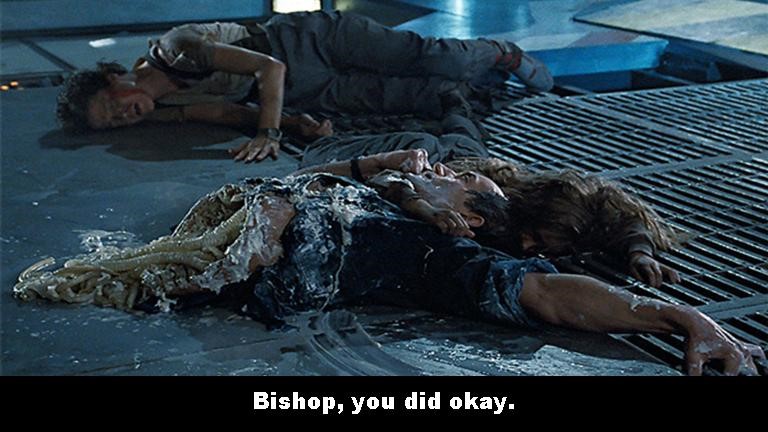

In Alien, the android Ash is portrayed as amoral, inhuman, and unmerciful. This is seen most clearly when Ash explains why he’s so fascinated by the murderous alien. He describes it as “a perfect organism… I admire its purity. A survivor… unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.” But in the sequel Aliens, the new android Bishop explained why Ash went berserk: “I prefer the term ‘artificial person’ myself… The A2s were always a bit twitchy. That could never happen now with our behavioral inhibitors. It is impossible for me to harm… a human being.”

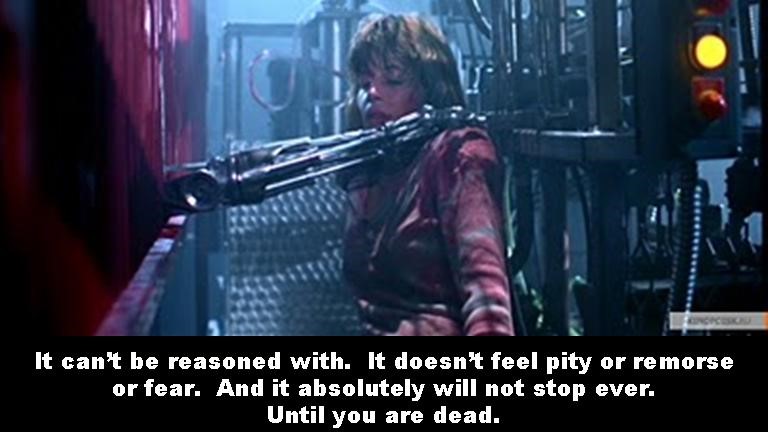

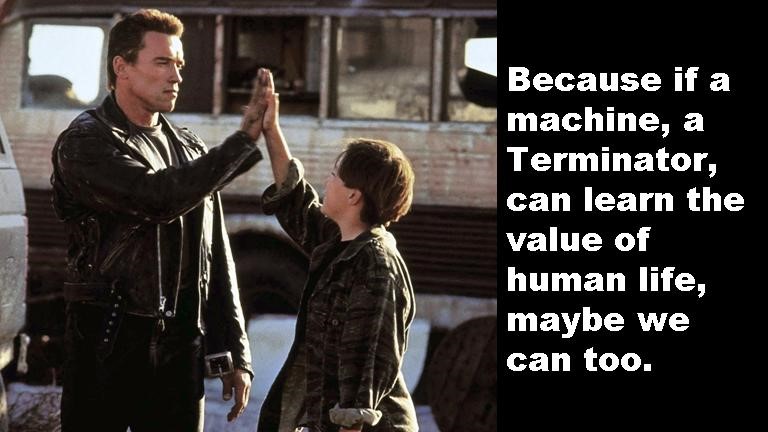

Lastly, in The Terminator, the Terminator is portrayed as a relentless, unfeeling, unemotional killing machine. While trying to convince Sarah Connor how much danger she was in, Kyle Reese explained that “It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity or remorse or fear. And it absolutely will not stop ever. Until you are dead.” But in the sequel, in the very last line of the movie, Sarah Connor gives the following message: “Because if a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too.”

How Will This Help Us Reach People for Christ?

Foreign missionaries, in order to reach the culture they’ve been called to, need to become students of that culture. In order to really communicate with the people in a way they can understand, missionaries need to do more than just learn their spoken language; they need to understand that culture’s intellectual history, its way of perceiving the world, and its customs and traditions. I would argue, then, for us, if we truly desire to reach our own Western society with the gospel, then it’s imperative we understand what our culture is going through and how its thinking became so confused. This will help us know what to say to our culture and how to say it. It will help us know what areas of thought our culture is currently struggling with so that we can show them how God’s Word provides the answers.

We need to show people that the Bible isn’t an old dusty book, irrelevant to modern man. It gives us the answers to life’s most pressing issues because its author is the Creator of life.

Our culture right now is experiencing a crippling tension. On the one hand, we’ve come to believe that we’re nothing but biological machines. On the other hand, everything inside of us screams that love is real, that morality is real, that we do make real, significant choices. Think of the biology professor who teaches her class that love is just a chemical reaction but then that night flies into a maddening rage when she finds out her husband has been cheating on her. Do you see the tension?

The only thing holding this tension together is an irrational leap; they believe in love, not because it makes rational sense to, but just because they want to. They’re driven to irrationality because they think logic and facts lead only to the despair of man-is-machine. And so our culture has reached out desperately for anything that could provide some sort of meaning, even if it’s an irrational leap of faith. This is driven home most powerfully at the end of Matrix Revolutions during the final battle between the machine program Agent Smith and Neo. After fighting back and forth for some time, Agent Smith, losing his patience, yells out: “Do you believe you’re fighting for something… more than your survival? Can you tell me what it is? Do you even know? Is it freedom or truth? Perhaps peace? Could it be for love? Illusions, Mr. Anderson. Temporary constructs of a feeble human intellect trying desperately to justify an existence that is without meaning or purpose! And all of them are as artificial as the Matrix itself… It’s pointless to keep fighting. Why, Mr. Anderson, why? Why do you persist?”

Neo responded with, in my opinion, a terrible answer. He answered Agent Smith’s taunting simply with “Because I choose to.” It’s as though Neo agrees that all those things are illusions: freedom, truth, peace, and love. But he just chooses to believe in them anyway. The issue is not what we choose to believe; the issue is what’s actually real. I wish Neo would’ve responded that “those things – freedom, truth, peace, and love – we fight for those things because they are real!”

I understand this is just a movie, but the fact is that this is exactly where our culture is at in its thinking; science and rationality have taught us that freedom, truth, peace, and love aren’t real, but yet we want to hold onto them. We choose to believe in them, not because we have good reasons to, but only because they give us some sort of purpose and meaning, while at the same time realizing that they’re ultimately an illusion. But to many thinking, sensitive people, this only leads to despair. Trying to muster this type of faith, a faith that goes against reason and rationality, is devastating. It’s like trying to convince yourself there’s a pink elephant in the room when clearly there isn’t. We weren’t meant to live with this sort of fragmentation in our thinking, nor the resulting tension it creates. And I don’t think it’s sustainable.

Of course, there’s one way to relieve the tension. We could drop the irrational leap of faith nonsense, just bite the bullet, and admit that love isn’t real. We could fully embrace the man-is-machine philosophy and be consistent with its implications. There has been some movement in this direction; consider Friedrich Nietzsche’s transvaluation of values, as well as eugenics, abortion, and euthanasia. There’s even the idea in some circles that modern medicine hinders human progress because it keeps the weak alive to pass on their inferior genes. We gasp at such a thought, but isn’t this just the progression Paul talked about? First God is dead.

…His invisible attributes, that is, His eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly seen since the creation of the world, being understood through what He has made. As a result, people are without excuse. For though they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God or show gratitude. Instead, their thinking became nonsense… (Rom. 1:19-22).

And when God is dead, morality is dead.

And because they did not think it worthwhile to have God in their knowledge, God delivered them over to a worthless mind to do what is morally wrong. They are filled with all unrighteousness… murder, quarrels, deceit… boastful, inventors of evil… unloving, and unmerciful (Rom. 1:28-31).

As Christians we need to speak to our society and tell them that there‘s another way to relieve the tension. We need to tell them that love is real, that you don’t have to take an irrational leap of faith to believe in it. We can explain to them that they were created by a Loving Person for the purpose of experiencing loving relationships with Him and with others. We can explain that love is not an illusion, that it’s actually a central part of ultimate reality, intrinsic to the eternal relationships between the three Persons of the Trinity.

It’s interesting to note that in the sequels discussed above, when Hollywood wanted to show that machines could really love, they had the machines sacrifice themselves to save others. In Aliens, the android Bishop died to save the little girl. In 2010, HAL was willing to die in the explosion so the humans could escape. In Matrix Revolutions, the Oracle let Agent Smith kill her so Neo could save mankind. In Terminator 2, the Terminator sacrificed himself to prevent the machines from taking over.

When Hollywood wanted to show that machines could love, they had them perform the greatest act of love there is: sacrificing yourself to save others. As Christians, we need to lovingly tell our culture that there’s a way out of this tension, that love is not an illusion, that it’s the foundation of ultimate reality, and that this love was demonstrated most clearly in that God sacrificed Himself to save us. That’s the message we have for the world.

![]()

© Adam Lloyd Johnson and Convincing Proof.